Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic neurological disease of the central nervous system in which the immune system attacks myelin –the protective coating around nerve fibers– and the nerve fibers themselves. The Inflammation and damage caused impairs nerve signaling to and from the brain and spinal cord, resulting in various symptoms such as fatigue, walking difficulty, numbness or tingling, spasticity, weakness, vision problems, bowel and bladder dysfunction, dizziness and vertigo, sexual problems, pain, cognitive impairment, emotional complications and depression (National Multiple Sclerosis Society-NMSS, 2018).

The causes of the disease are attributed to genetic susceptibility combined with environmental factors. While MS can strike all ages, it is typically diagnosed in the ages between 20 and 50 years, with women being affected twice or thrice as much as men (NMSS, 2018).

The symptoms of MS and their effect on real-life decrease the patients’ Quality of life (QoL) in terms of physical and occupational functioning, psychological state, social interaction, engagement in leisure activities, and fulfilling typical roles in life. The consequences may even include reduced employment or unemployment (Zwibel and Smrtka, 2011).

QoL is a subjective and multidimensional concept defined with respect to the context where it is used (Isaksson, Ahlström and Gunnarsson, 2005). It refers both to personal satisfaction/joy and the ability to function well and be productive within society (Zwibel and Smrtka, 2011), including physical, emotional and cognitive health, sense of well-being, performing well and enjoying social roles (Theofilou, 2017).

For people suffering from chronic diseases, QoL is mainly influenced by health issues rather than by non-health issues (Spilker and Revicki, 1996 in Theofilou, 2017). Thus, health-related QoL (HRQoL) constitutes an important measure of the effect that chronic illness has on sufferers which is used to inform their medical care, rehabilitation, and nursing. It comprises the aspects of QoL affected by the disease (Isaksson et al, 2005). Measures of HRQoL can be valuable both in clinical practice and in the process of evaluating MS treatment strategies.

HRQoL measures align with the functional-based approach to QoL assessment, providing information on disease severity, symptoms, functional restrictions and the impact of disease on society. These measures primarily concern experts and therefore their content is designed by experts (McKenna, 2005).

On the other hand, needs-based QoL measures can inform on the overall impact of disease and its treatment from the patients’ perspective (McKenna, 2005). In the needs-based approach QoL is defined in terms of the individual’s capability to fulfil certain human needs as a result of their disease. Functioning is important to the extend it allows needs fulfillment. The content of needs-based QoL instruments is derived from patients through in-depth qualitative interviews (Doward and McKenna, 2004).

The two kinds of measures are, of course, complementary rather than alternative (McKenna, 2005).

HRQoL instruments are also distinguished in generic and disease-specific. Generic scales mostly assess basic HRQoL issues potentially associated with any disease and enable researchers to compare between different diseases and interventions, while disease-specific HRQoL scales are designed for individuals with particular diseases and tap specific health-related effects of the disease concerned (Bandari, Vollmer, Khatri, & Tyry, 2010).

Since generic instruments cannot reflect health aspects which are unique to a disease, they may not be able to detect change in these aspects (Hobart, Freeman, Lamping, Fitzpatrick, and Thompson, 2001). Concerning MS in particular, generic scales have limited ability to detect HRQoL differences among MS patients (Bandari et al, 2010).

One such scale, the Short Form-36 (SF-36) (Stewart and colleagues, 1988) is widely used in different chronic conditions because it is simple, comprehensive and assesses the overall effect of disease besides physical and emotional limitations, physical and social functioning, pain, vitality, mental health, and general health aspects. However, it cannot capture subtle disease-specific changes –concerning, for instance, bladder, bowel, sexual, and cognitive function in MS– and thus, on its own, may not be sufficient for MS patients. Besides, in groups with small differences in MS severity the usefulness of SF-36 was undermined by significant floor and ceiling effects (i.e. over 20% of the participants chose the highest or lowest value on the scale) (Hobart et al, 2001). Floor and ceiling effects are minimized by using disease-specific HRQOL instruments (Bandari et al, 2010).

A lot of research indicates that disease-specific scales provide better evidence about the influence of a disease on HRQoL compared to generic scales which are often insensitive with respect to MS patients (Bandari et al, 2010). An MS-specific scale is more appropriate, as there are particular issues that contribute much more to the QOL of patients suffering from MS. Besides, an MS-specific measure will be more sensitive to changes in the particular condition (Berlim and Fleck, 2003).

If, however, we want to assess the overall influence of the disease (or its symptoms) on QoL, it is strongly suggested to use a generic QoL instrument as main outcome, and complement the data –where appropriate– with illness-specific measures (Berlim and Fleck, 2003). For example, in studying MS, SF-36 can be supplemented with other measures such as MSQLI and MSQOL-54 that capture ways in which MS more specifically affects QoL (fatigue, vision etc.) (NMSS, 2018).

As regards evaluating the effectiveness of an intervention for MS patients, the overwhelming nature of this disease calls for maintenance of HRQoL in the long-run. The HRQoL scales to be used need to provide accurate and consistent measurements of QoL throughout the progression of the illness, which becomes more difficult when interventions are applied that influence QoL either positively or negatively (Bandari et al, 2010). HRQoL measurements can reveal which patients mostly profit from the intervention. For example, in some cases patients with low HRQoL may benefit more by MS interventions than patients with high HRQoL (Bandari et al, 2010).

Most established HRQoL scales have not been validated for longitudinal assessment of HRQoL which is required in the present case. Besides, when assessing HRQoL changes in people over time, apart from changes in QoL there may also be changes in how these people perceive health and QoL. This so-called “response shift” may significantly alter the relative value people place in various HRQoL dimensions, and induce devaluation of treatment effects (e.g. in Schwartz, Coulthard-Morris, Cole, and Vollmer, 1997), thus influencing the validity and reliability of a HRQoL scale over long periods of time.

The above considerations call for measures that can assess HRQoL in MS patients accurately and completely. MS-specific scales like MSQOL-54, MSQLI, and MusiQOL, can detect true changes in the HRQoL of MS patients and for this reason it has been suggested that they should be included systematically in health-care programs of MS patients (Bandari et al, 2010).

These instruments provide elaborate assessment of MS severity and impact of treatment from the perspective of both patient and clinician. Systematic use of such tools in clinical research and practice can help define the relationship between MS treatments and MS patients’ HRQoL and thus contribute to the best use of MS treatments (Bandari et al, 2010).

In the present case I would strongly recommend the use of Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Inventory (MSQLI) which has been relatively widely used and validated in various clinical studies. It is superior to MSQOL-54 which has known weaknesses, such as lack of sensitivity in the assessment of physical functioning especially for moderately or severely disabled MS patients undergoing longitudinal assessment of HRQοL and lack of established disease-specific subscales. MSQLI also outweighs MusiQOL as the latter has had limited usage in MS treatment studies (Bandari et al, 2010).

MSQLI has well understood psychometric properties, and provides extensive pertinent information (Bandari et al, 2010).

Being disease-specific, MSQLI has been developed following the needs approach, thus having a focus on the specific needs interfered with by Multiple Sclerosis which makes it very relevant and acceptable to the patient group. The fact that it reflects the concerns of the patient group, ensures good content validity, maximizes the instrument’s acceptability to respondents and minimizes missing data (Doward and McKenna, 2004).

Content validity for the MSQLI has been confirmed by assessing the instrument’s adherence to a conceptual model of the effect of MS, and reviews of MS neurologists and allied health professionals, HRQoL specialists, patients, and caregivers (Ritvo, Fischer, Miller, Andrews, Paty, and LaRocca, 1997).

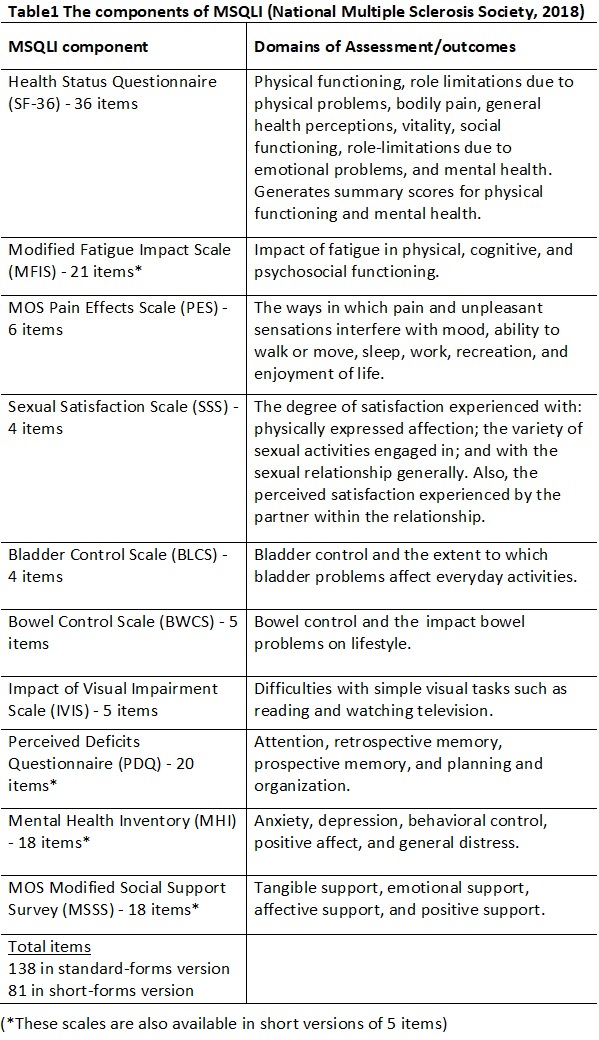

The MSQLI instrument is both generic and MS-specific (Fischer, LaRocca, Miller, Ritvo, Andrews, and Paty, 1999), as it comprises the widely-used generic scale SF-36 complemented by 9 established disease-specific scales which evaluate fatigue, pain, bladder function, bowel function, mental health, perceived cognitive function, visual function, sexual satisfaction, and social support. Table1 summarizes the components of MSQLI.

In the standard forms version, completion time is about 45 minutes which can be reduced to 30 minutes when the short forms version is used.

In our case, I suggest using the abbreviated versions available in order to reduce administration time and resources –considering that their psychometric properties are comparable to those of the standard versions (NMSS, 2018).

Patients can complete the self-report questionnaires with little or no intervention from an interviewer (who should be trained in basic interviewing skills and in the use of this instrument), except from cases with visual or upper extremity impairments where MSQLI may need to be administered as an interview.

The modular, symptom-specific structure of MSQLI enables cross-disease comparisons of both generic sections and disease-specific symptoms that may influence HRQoL (Fischer et al, 1999). This is crucial for the case of this intervention which requires QoL assessment at baseline, end of programme, six and twelve month follow-up.

The subscales of the MSQLI have good internal consistency reliability as the lowest alpha is 0.67 (for social functioning on SF-36) while other coefficients range from 0.78 (BWCS) to 0.97 (MSSS). The SF-36 test-retest reliability ranges from 0.60 (social functioning) to 0.81 (physical functioning) (NMSS, 2018).

Reliability and construct validity has been established by rigorous assessment in a field test with 300 North American patients having definite MS and a wide spectrum of physical impairment (Fischer et al, 1999). Moreover, the MSQLI has been validated for use in MS patients of older ages or with considerable cognitive impairment (Bandari et al, 2010).

MSQLI has been effectively used for HRQoL assessment in various studies of MS disease-modifying treatments, for example, concerning the benefit of interferon beta-1a on the progression of MS-related in secondary progressive MS (Cohen, Cutter, and Fischer, 2002) and the Effects of Natalizumab (Rudick, Miller, and Hass, 2007).

Among the advantages of MSQLI is that it assesses several MS-specific dimensions such as visual function, bowel and bladder control and has a modular structure which enables flexible administration. So it allows the assessment of various problematic symptoms which may inform clinical discussion and give rise to treatment of symptoms along with disease-modifying treatment (NMSS, 2018).

In the present case, by comparing the HRQoL outcomes at designated time-stages, the clinical service will be able to determine whether the particular intervention actually improves the HRQoL of MS patients in the long-run. The effect of the intervention will be revealed on objective measures of disease and on the patients’ QoL.

Terms and Conditions for Republishing Content

Article Author: Panagiota Kypraiou MSc Health Psychology, MBPsS - Body & Gestalt Psychotherapist (ECP) - Body Psychotherapy Supervisor - Parents' Education Groups Coordinator https://www.psychotherapeia.net.gr

References

Bandari, D. S., Vollmer, T. L., Khatri, B. O., Tyry, T. (2010). Assessing Quality of Life in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. International Journal of MS Care, 12, 34–41

Berlim, M.T. & Fleck, M.P.A. (2003). Quality of life: a brand new concept for research and practice in psychiatry. Rev Bras Psiquiatr, 25(4), 249-52

Contentti, E. C., Genco, N. D., Hryb, J. P., Caspi, M., Chiganer, E., Di Pace, J. L., López, P. A., Lessa, C., Caride, A. and Perassolo, M. (2017). Impact of multiple sclerosis on quality of life: Comparison with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery, 163, 149-155

Doward, L.C., and McKenna, S.P. (2004). Defining Patient-Reported Outcomes. Value in Health, 7(1)

Fischer, J. S., LaRocca N. G., Miller, D. M., Ritvo, P. G., Andrews, H. and Paty D. (1999). Recent developments in the assessment of quality of life in multiple sclerosis (MS). Mult Scler., 5(4), 251–259. Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/135245859900500410?journalCode=msja

Hobart, J., Freeman, J., Lamping, D., Fitzpatrick, R., and Thompson, A. (2001).

The SF-36 in multiple sclerosis: why basic assumptions must be tested. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 71, 363–370

Isaksson, A-K., Ahlström, G. and Gunnarsson, L-G. (2005). Quality of life and impairment in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 76, 64-69. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.029660

McKenna, S. P. (2005). Needs-Based Quality of Life (QoL): More Clarity than Claret! The Journal for the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, 8(1), 84–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.08105.x

National Multiple Sclerosis Society. (2018). Definition of MS. Retrieved from https://www.nationalmssociety.org/What-is-MS/Definition-of-MS

National Multiple Sclerosis Society. (2018). MS Symptoms. Retrieved from https://www.nationalmssociety.org/Symptoms-Diagnosis/MS-Symptoms

National Multiple Sclerosis Society. (2018). Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Inventory (MSQLI). Retrieved from https://www.nationalmssociety.org/For-Professionals/Researchers/Resources-for-Researchers/Clinical-Study-Measures/Multiple-Sclerosis-Quality-of-Life-Inventory-(MSQL

National Multiple Sclerosis Society. (2018). Who Gets MS? (Epidemiology). Retrieved from https://www.nationalmssociety.org/What-is-MS/Who-Gets-MS

Ritvo, P. G., Fischer, J. S., Miller, D. M., Andrews, H., Paty, D. W., and LaRocca, N. G. (1997). MSQLI Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Inventory: A User's Manual. The National Multiple Sclerosis Society

Rudick, R. A., Miller, D., & Hass, S. (2007). Health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: effects of natalizumab. Ann Neurol., 62, 335-346

Schwartz, C. E., Coulthard-Morris, Cole, L. B., and Vollmer, T. (1997). The Quality-of-Life Effects of Interferon Beta-1b in Multiple Sclerosis: An Extended Q-TWiST Analysis. Arch Neurol., 54(12), 1475-1480. doi:10.1001/archneur.1997.00550240029009

Theofilou, P. (2017). Lecture Notes M.Sc. in Health Psychology, Quality of Life

Zwibel, H. L. and Smrtka, J. (2011). Improving Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis: An Unmet Need. The American Journal of Managed Care, 17(5)